Patriots Face Music in Loss to Saints, Miss Playoff Dance

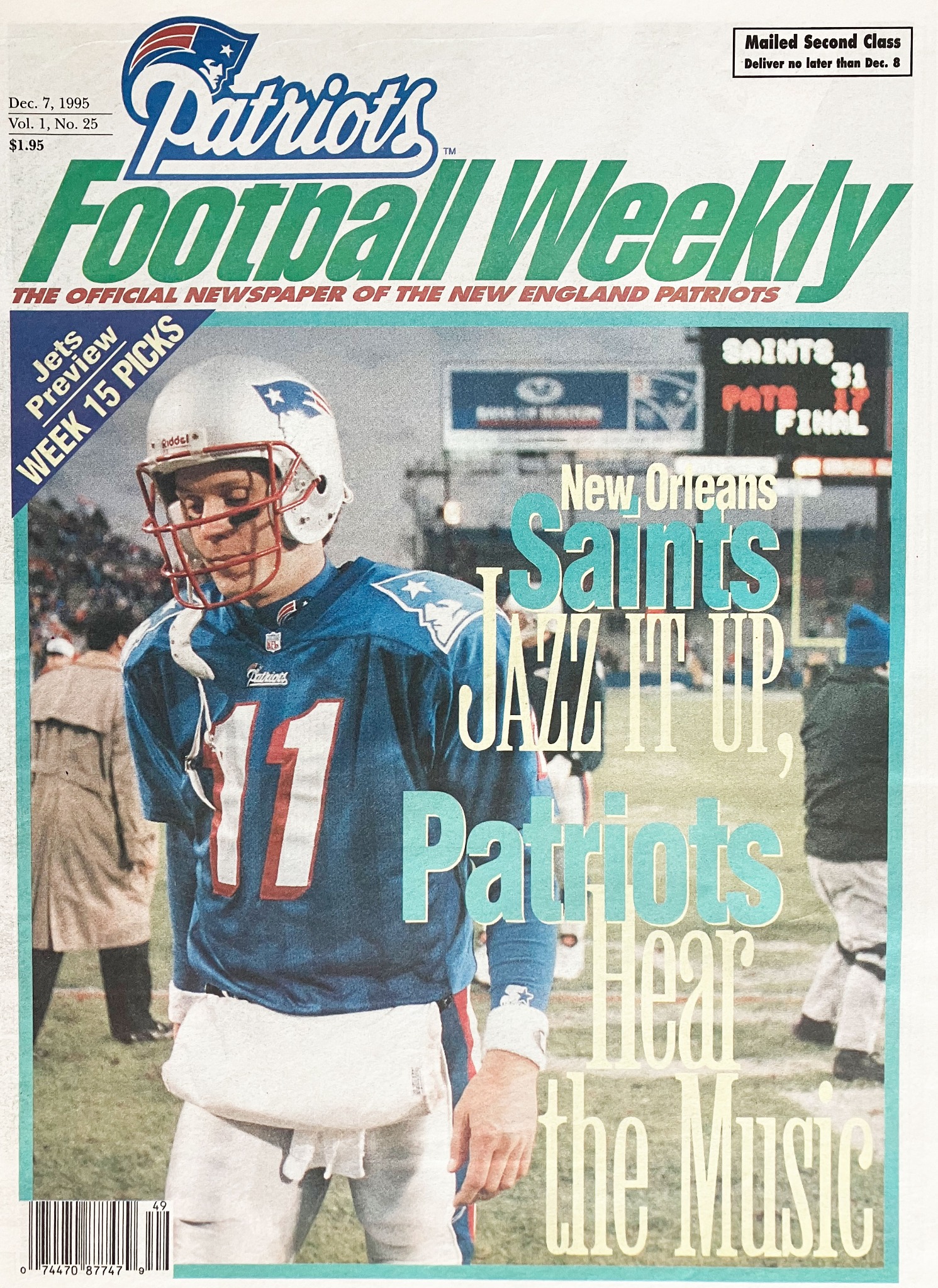

The day the Patriots’ playoff music died, Murphy’s Law, the Law of Averages and rookie cornerback Ty Law’s inexperience finally caught up with New England, sending the New Orleans Saints back to Poydras Street with their playoff hopes – and respect – intact after a 31-17 road victory in Foxboro.

Murphy’s (blitzing) Law did in the would-be AFC East contenders, when anything that could go wrong did go wrong when New England blitzed. The Law of Averages dictated that the Patriots (5-8) couldn’t win ad infinitum when rookie runner Curtis Martin rushed for 100 yards or more. Finally, defensive back Ty Law, playing the “cursed corner” vacated by Maurice Hurst two weeks ago, suffered his overdue rookie indoctrination into the “I Passa U” fraternity at the hands of veteran Saints quarterback Jim Everett and wideout Quinn Early.

In the wake of a respectable start in Buffalo after the unceremonious axing of Hurst, Law was picked on – and picked off – by the Saints, who improved to 6-7. The rookie was one of the last Patriots seen on the television screen on three New Orleans touchdowns.

Law was picked on by Everett on a 50-yard bomb to a streaking Early down the left sideline, leaving the University of Michigan blue-chipper red-faced in the third quarter. Law, who had drawn a firm, cross-field bead on fullback Lorenzo Neal on his 69-yard touchdown reception in the fourth, was picked off by wideout Michael Haynes’ borderline clip that paved the way for Neal’s touchdown. Law was also faked out of his silver knickers on a 66-yard touchdown jaunt by halfback Mario Bates in the fourth.

The salivating Everett (17 of 26 for 293 yards, 2 TDs, 1 INT) could hardly contain his enthusiasm – or conceal the Saints’ game plan – during New Orleans’ initial offensive series. On the Saints’ first play, way back at their lucky 13-yard-line, Everett beat Law with a nine-yard completion to Early. On fourth and inches moments later, the Saints orchestrated a masterful reverse to Law’s side for a 13-yard gain, setting the table for the 50-yard Everett-to-Early scoring connection.

“I want to own that side of the field,” Law said after the game, but that didn’t stop Early from renting Law’s turf all afternoon. Everett, who wasn’t sacked all day, dropped back into a very secure pocket and launched a perfectly placed spiral into Early’s waiting hands in the north end zone for an early 7-0 lead.

After dissecting the Buffalo game film, Early and Everett noticed Law’s tendency to “squat” on a receiver, awaiting the wideout’s break. This time, though, Early threw Law a curve, racing right by him.

“If the corners are [playing] off,” noted Early, “we don’t go deep that much. [We go deep] only if they press. We noticed that when we ran breaking routes, [Law] was sitting, waiting on the breaking routes. We figured if we went up[field], just ran a goal route, that we might be successful with it.

“Everett just made a great throw,” added Early, who paced New Orleans with five receptions for 92 yards. “He put the ball just where it needed to be. I got by [Law] and that was it.”

That wasn’t it, at least as far as the Saints were concerned. New Orleans kept testing Law (3 total tackles) but failed to burn him deep again. The youngster did exact some measure of revenge against his tormentor a quarter later, snaring Everett’s underthrown pass to Early at the New England seven with less than 30 seconds remaining in the half. New Orleans guard Jim Dombrowski and halfback Derek Brown brought down Law 38 yards later, inciting a WWF grudge match in front of the Patriots’ bench.

The designated safety on any interception, Everett knew that defensive end Ferric Collons was just executing his duties when he began to lock horns with him. It was the blow to the head that Everett – and the referees – took exception to, as the pair then locked up, Greco-Roman style, near midfield. The 212-pound “lightweight” in the three-fall showdown, Everett pinned the 285-pound Collons and was jawing with him, facemask to facemask, before the pair was separated and Collons was flagged for unnecessary roughness.

“I don’t know if he knows that I’m a grappler,” joked Everett, a four-year wrestling letterman at El Dorado High in Albuquerque, N.M. When a press-box pundit observed that Collons probably won’t “mess with” him again, Everett quickly chuckled and said, “Oh, he probably will.”

No one can accuse New England of a spiritless effort on Sunday. A brain-locked effort, maybe, but not another going-through-the-motions showing like the Denver debacle. The brain-lock part came in the fourth, with both clubs staggering to the finish line in a 17-all deadlock. Matt Bahr evened the proceedings with a 39-yard field goal to open the final quarter, capping a 12-play, 40-yard drive that consumed about six-and-a-half minutes.

At this point, the Patriots must have felt good about their chances. After all, Martin already had 103 rushing yards in the bank, a sure indicator of a New England win during the team’s first dozen games. And let’s not forget the wind at the Patriots’ backs in the fourth. With New England quarterback Drew Bledsoe’s arm and a healthy gale, the prospects for victory certainly looked bright.

Then, before one could say fleur de lis, the Saints struck for 14 points on three plays in a grand total of 39 seconds. After tucking the game away in less than a minute, New Orleans still managed to hold onto the ball for almost seven minutes in the final quarter. Patriots’ linebacker Willie McGinest, who was last seen skulking up the Patriots’ runway, was the prime culprit on the Saints’ two big plays.

“Mentally, we were ready to go in terms of the emotional aspect of the game,” said Patriots coach Bill Parcells. “But we just didn’t deliver when it counted. . . . All we had to do was play solid defense for one more quarter and we had a chance to win. But we didn’t do that.”

Any player with a love for the game will you that nothing – nothing – on the football field beats silencing a hostile crowd on the road. Two plays after Bahr knotted the score at 17-17, the boys from the bayou efficiently muffled the Foxboro Faithful.

“Mentally, we were ready to go in terms of the emotional aspect of the game. But we just didn’t deliver when it counted. . . . All we had to do was play solid defense for one more quarter and we had a chance to win. But we didn’t do that.”

Everett, who repeatedly torched New England’s blitzing defenders, evaded yet another Patriots’ blitz by stepping up into a collapsing pocket and hitting a wide-open Lorenzo Neal in the right flat, where McGinest was conspicuously absent. The tortoise-like Neal somehow managed to outrace the Patriots’ secondary on his way home to the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, taking advantage of tight end Irv Smith’s springing block and Haynes’ near-clip of Law. The drive: two plays. Time elapsed: 26 seconds.

“I thought we did a great job of picking up the blitzes all day,” said Everett, who rendered a first-quarter Patriots’ blitz impotent by hooking up with Smith for a 43-yard pickup, which set up the Saints’ second touchdown. “Irv Smith (5 catches, 67 yards) caught a few balls that were hot-blitz pickups. . . . Early in the season, we wouldn’t have picked [the blitz] up as well as we did today.”

What the Patriots’ defense did was collapse completely on New Oreleans’ next series. After Bahr booted a rare clanker, wide left, with 8:43 remaining in what was effectively New England’s season, New Orleans worked a little voodoo magic by calling a play that worked to perfection.

Everett credited Saints’ running backs coach Jim Skipper with the game-clinching call, a touchdown run around right end by Bates, who collected 66 of his game-high 123 rushing yards on the play.

On the first play from scrimmage, Bates simply edged by Smith on the strong side behind a crunching block by Neal. McGinest, MIA again, misjudged the play. The shifty Bates performed a shake-and-bake move to elude Law and then stiff-armed strong safety Terry Ray on his way to the end zone and a 31-17 cushion.

“The guys felt really good about the play and they executed it,” said Everett. “I know that Joe Namath made his calls in the Super Bowl, but it’s great when you have 10 guys other than yourself saying, ‘This is going to the ‘zone.’

“I know Irv Smith started it and he got Lorenzo [Neal] and the offensive line cranked up,” added Everett. “They said, ‘Let’s just take this one,’ and Mario [Bates] did the rest, thanks to a great effort by everybody. They called [the play] out. It was one of the first times that ever happened to me in my career; when all the guys were calling, ‘This is going to take it.’”

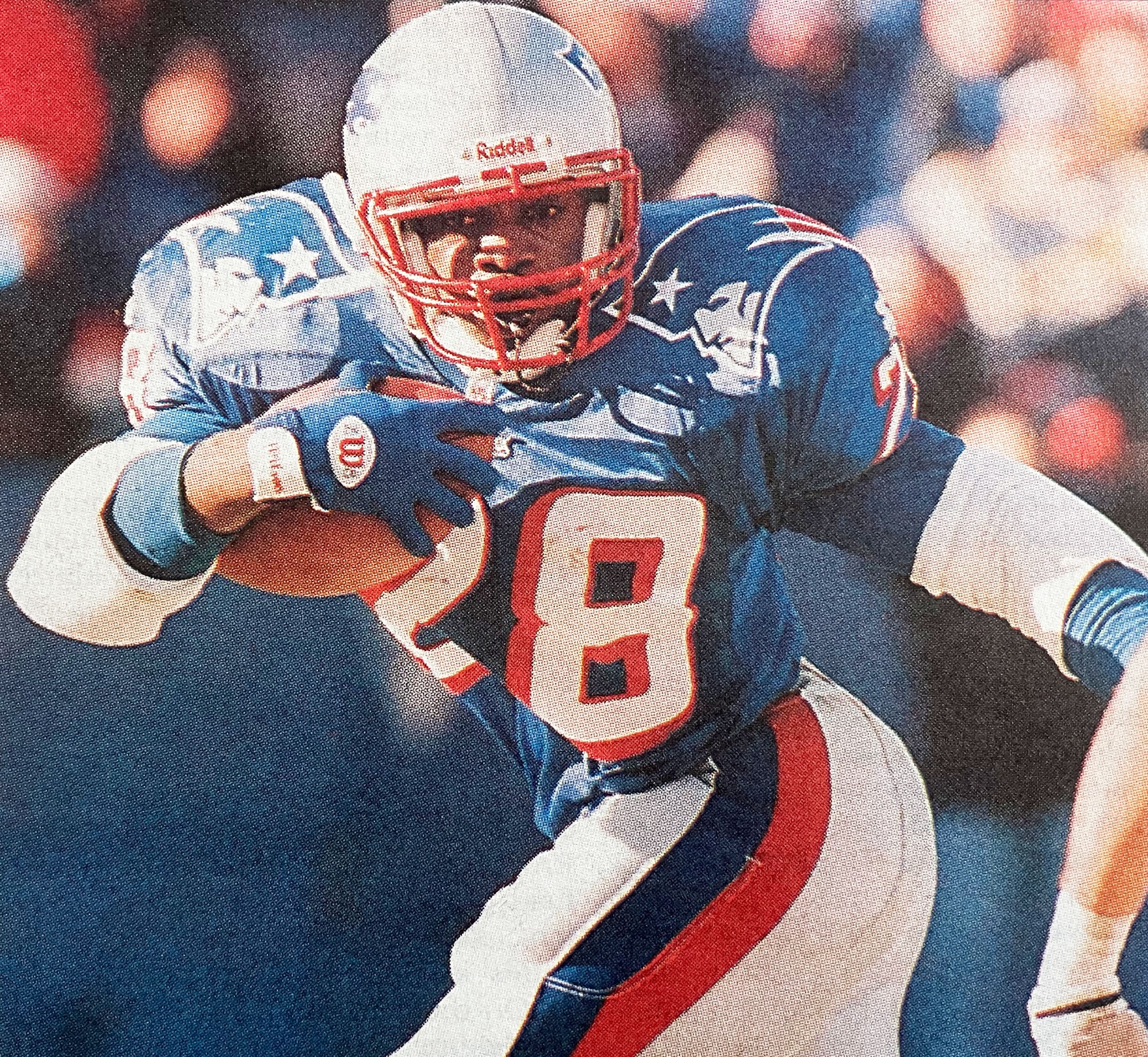

Before the Saints “took it” in the fourth, New England was positioning itself for another “Parcellian” December rush for the playoffs behind Martin, but the Law of Averages was the only tackler that Martin failed to elude.

Martin broke the 1,000-yard barrier the old-fashioned way – in 12 games with a 100-plus-yard effort – a week prior at Buffalo, boosting the Patriots’ record to 5-0 when he runs for more than 100 yards. For the first time this season, a three-figure rushing performance from Martin – who ran 31 times for 112 yards – wasn’t enough to spur the Patriots to victory.

Conversely, the Patriots did play true to form when run over by an opponent: New England is now 0-2 when butting heads with a 100-yard rusher. Bates zoomed past a hundred yards on Sunday, the first time the Patriots allowed a 100-yard rusher since Carolina’s Derrick Moore racked up 119 yards in the Panthers’ 20-17 October victory.

None of this should really come as a surprise. After all, the NFL powers-that-be have achieved their goal of true parity this fall, but arguably at the cost of quality football. On a day when the lowly Redskins toppled Dallas and a hundred-yard effort by Martin went for naught, nothing is a sure thing in the dazed-and-confused NFL this fall.

And just when Parcells thought he had his finger on the pulse of his club, just when he thought he may have reached some level of psychological understanding of his young team, the schizophrenic Pats figured out a new and novel way to lose, leaving a resigned Vincent Brown to say, “We never expected to be here right now,” and a disgruntled Parcells to note, “I’m just a little bit disgusted with what went on today.”

In effect, the Patriots have left Parcells little choice but to – like Forty-Niners coach George Seifert – blame it on the Bossa Nova.

Post a comment