When Nantucketers Rode the Rails

From Cape Cod Life Magazine

Unlike many of Nantucket’s quaint cobblestone streets, which have well-known histories, Easy Street’s origin is as murky as the stubborn fog that frequently envelops this waterfront roadway. What can be said about the picturesque one-way is that the town officials who chose the name—at some point between 1918 and 1923—must have had a wry sense of humor.

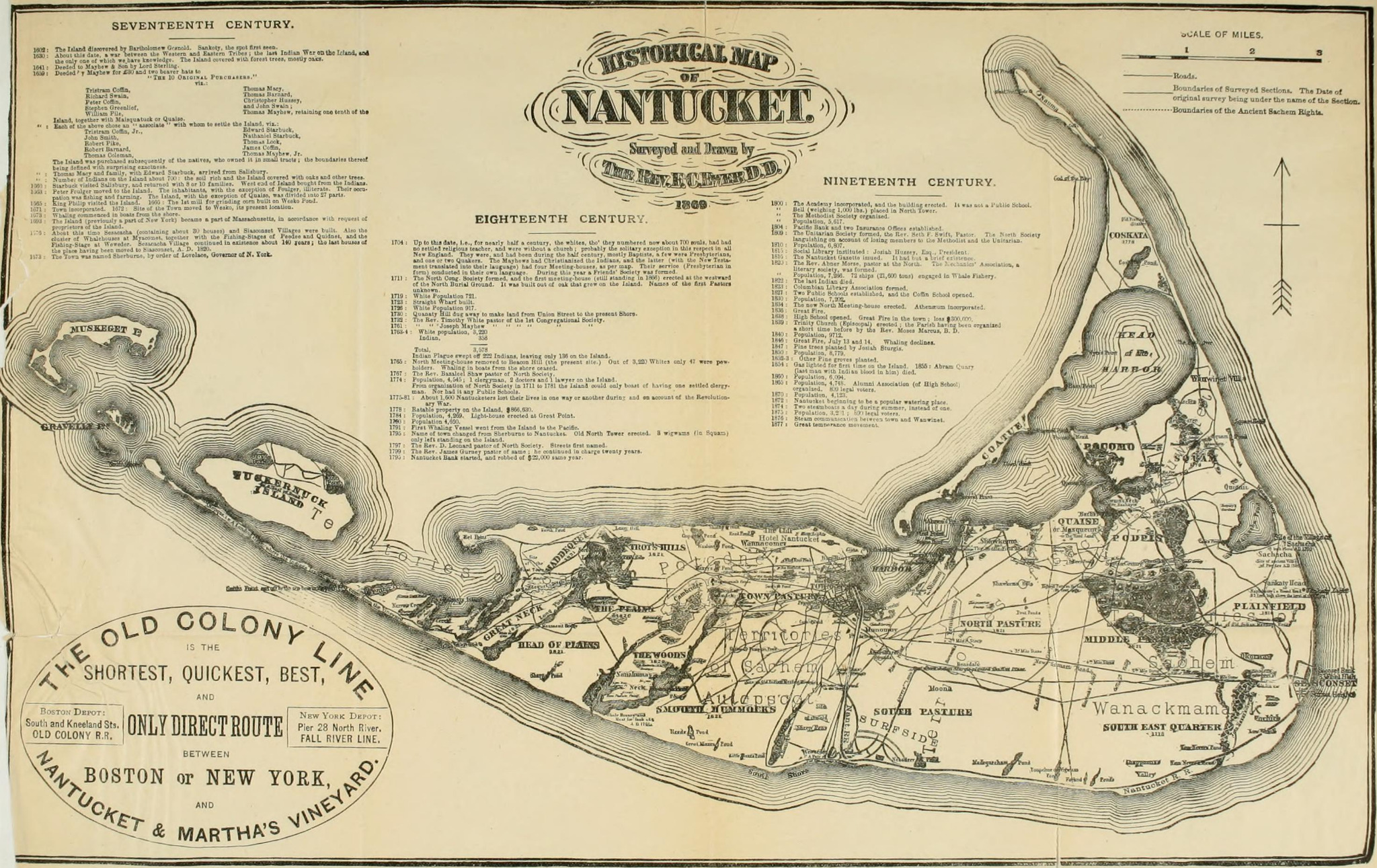

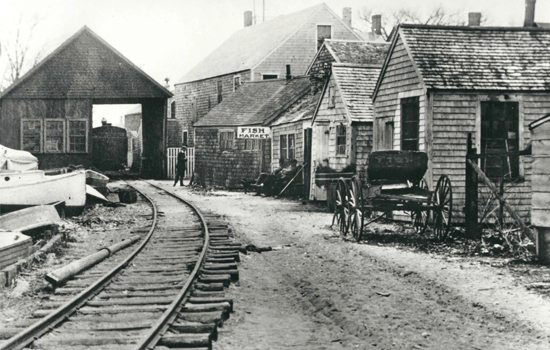

Easy Street, which boasts a stunning view of Nantucket Harbor, was built on the path of the dearly departed Nantucket Railroad, a privately funded enterprise that operated—in fits and starts, but mostly fits—from 1881-1918. Although it ran in the red for most of its checkered history, the Nantucket Railroad had a rich history of derailments, de-coupled cars, engine failure, shifting tracks, crashes, and other calamities; miraculously, only two people were killed by the train during its 37-year run.

In short, the Nantucket Railroad never led to “Easy Street” for anyone, especially the company’s owners and investors.

According to Mike Harrison, chief curator of the Nantucket Historical Association, 19th-century railroads were rarely profitable ventures. But even by the day’s standards, the Nantucket Railroad was the Rodney Dangerfield of railways. In other words, it got “no respect,” especially from the islanders.

According to separate 1909 editorials in Nantucket’s Inquirer and Mirror newspaper, the railroad was “termed something of a cross between a farce and philanthropy,” and “for years has been the object of ridicule in both rhyme and story.”

While locals did use the train, which they called “the cars,” the narrow-gauge railroad was originally built to transport potential home buyers and investors from Nantucket Town to new seasonal developments that were sprouting up on the island’s south shore. Many of the property developers also doubled as railroad investors.

“Various entrepreneurs were creating seaside resort communities at Surfside, Tom Never’s, and ’Sconset, and they needed a way to get people from here to there,” says Lee Saperstein, a retired college professor who is leading an effort to convert the old railway path into a historic “rail trail” for walkers, runners, and bicyclists. “Some of those real estate developments did not succeed, but some did. ’Sconset, a fishing village, was relatively successful, becoming an artist’s colony right around the [end] of the [20th] century.”

At best, Nantucketers’ feelings about their “iron horse” were complicated from the start. Proud Nantucket was once the whaling capital of the world, but when the whaling industry collapsed in the mid-19th century, the local economy was decimated and the island lost two-thirds of its population.

“After the War of 1812, Nantucket was the Saudi Arabia of liquid fuels and this was a very wealthy island,” says Saperstein. “But the advent of Pennsylvania’s oil fields and [Edwin] Colonel Drake’s oil drill in the mid-1800s, the big fire we had [in Nantucket Town] in 1846, and the Civil War all brought about the collapse of the whaling industry. As a result, Nantucket became a severely diminished community.”

Searching for a way to revive their flailing economy, entrepreneurial Nantucketers recognized that the island’s beauty and ocean air might hold some appeal as a summer resort. Inns, hotels, and rooming houses began to proliferate on the island in the latter half of the 1800s. So while some visionary islanders viewed a railroad as a means to expand resort development, others believed it was a boondoggle.

“Many islanders felt that the railroad shouldn’t be built,” says Mike Harrison. “When Town Crier Billy Clark drove the first spike of the railroad [on Steamboat Wharf on May 31, 1881], the businesses that opposed the railroad hung black crepe from their windows the next morning.”

It was only when the Nantucket Railroad was dismantled in the spring of 1918, and its scrap metal drafted to support Allied Forces in France during World War I, that islanders seemed to have a change of heart about their rail line. When writing about the railway’s dismantling in his 1972 book The Far-Out Island Railroad: Nantucket’s Old Summer Narrow-Gauge, author Clay Lancaster best captured Nantucketers’ love-hate relationship with their railway.

“Those who loved and honored the old railroad preferred to think of it as riding off to war, to serve its country. It was on its way to France, to the Marne River Valley, to help block the final German drive on Paris,” wrote the deceased Lancaster, a noted architectural historian who spent considerable time on the island. “Considering its past record and the fact that the war was to be over in six months, there is only one reasonable role the little Nantucket line could have played in the conflict. This was for it to have been given to, set up for, and used by the Central Powers. It would have contributed substantially to their humiliating defeat.”

Although humiliating railway incidents caused Nantucketers repeated headaches over the decades, Harrison believes that “feelings may have changed over time. I suspect that there might have been some romance attached to the railroad by 1918, but not enough for anyone to try and keep it going.”

For three ownership groups, that was always the challenge—to keep the railroad going. Whether operating as the Nantucket Railroad (1881-1894), the Nantucket Central Railroad (1894-1909), or the Nantucket Railroad again (1909-1918), the island line’s exceptional operating difficulties can be traced to a few key factors: First, it was built on the cheap, with second-hand equipment being used for more than three-quarters of its lifespan. Second, the track on the Surfside-to-’Sconset leg, which was laid on coastal sand and operated from 1881 to 1894, would often wash out. Third, for the most part the train ran only during the summer months, severely limiting its profit potential while boosting start-up maintenance costs each spring.

So when residents realized that they were losing their line, they voted to repeal the island’s Automobile Exclusion Act in May 1918, effectively driving the final rail spike into the Nantucket Railroad’s coffin.

Despite the original railroad’s spotty history, many contemporary Nantucketers would welcome rail service back to the island. The Grey Lady’s recent property boom, which has seen the price of modest-sized homes spike into the millions, has also seen a proportionate boost in auto traffic. “It would be great to have a train on the island today so we wouldn’t have all these bloody cars,” says Libby Oldham, a Nantucket Historical Association (NHA) research associate.

Even though nearly a century has passed since the last train raced across The Moors in 1917, bound for ’Sconset, there are echoes of the Nantucket Railroad all over the island—if one knows where to look.

The “loudest” echo sits at the base of Main Street, where The Club Car Restaurant and Bar has operated since 1977. When the railroad folded in 1918, an old Pullman car was left alongside the train station. The car was converted into Allen’s Lobster Grill and Diner, which served locals and tourists for more than four decades before the current ownership team bought the old station and car.

The NHA also boasts a substantial collection of Nantucket Railroad artifacts, most notably the bell from Dionis, the railroad’s first engine. Named for the wife of Tristram Coffin, one of the island’s early settlers, Dionis proudly served for about two decades before being taken off the line.

The remaining echoes of the far-out island railroad are a bit more subtle, according to Saperstein, a Rhodes Scholar who taught mining engineering at Penn State and the University of Kentucky. “For instance, look at the gentle curve of the Easy Street bulkhead,” says Saperstein, a commanding presence as he saunters along the Nantucket waterfront. “Trains can’t take hard turns, so the route from Steamboat Wharf takes a soft turn along the water.”

Just beyond the line’s Goose Pond Causeway, which is now a dirt walking path, sits Hatch’s Package Store, which is situated at an odd angle from Orange Street. “That’s because the railroad right of way wasn’t owned by Hatch’s when it was built,” says Saperstein. “So the business owners had to build parallel to the old railway.”

The rail path also runs diagonally behind the Cape Cod Five Cents Saving Bank on Lower Pleasant Street, and a little further southeast, more evidence of the railway is uncovered by Saperstein alongside Hinsdale Road. “Hinsdale has survived from the days when it was the maintenance way alongside the railroad,” says a spry Saperstein, as he mounts a four-foot tree- and brush-covered hill. Upon reaching the top, he reveals that “this was the roadbed.”

Building the Nantucket Railroad, as Saperstein points out, was a remarkable engineering feat that played a pivotal, albeit colorful, role in the island’s transformation from a whaling economy to today’s world-class resort community. Along the way, despite its frequent flops and failures, the “far-out island railroad” somehow captured the imaginations of generations of islanders and vacationers, as described by an unknown writer in the “Here and There” column that appeared in the March 16, 1918 Inquirer and Mirror.

“Won’t it seem lonesome next summer not to hear the sound of Dionis’ bell as she crosses the Goose Pond, or to hear her cheerful toot as she mounts the grade at Hinsdale, bound across the moors to ‘Sconset! The little train will be both a miss and a loss to Nantucket. Most everybody had rather hear Dionis whistle than Ford honk, for Dionis was unique in more ways than one, and when she goes to the junk-heap there will be a great big vacant spot in Nantucket’s summer life.”

Joe O’Shea is a freelance writer from Bridgewater, Mass.

Post a comment